Yoga for the Psoas – Healthy Lower Back and Emotional Opening

Apr 21, 2022

The psoas muscle that allows us to stand proudly upright, is located deep within the front hip joint and lower spine. As a potential source of lower back and hip pain, to simply view its involvement in a mechanistic way is to only see a fraction of the bigger picture. As the only muscle that connects top and bottom body, its role in bipedal standing and walking is critical for alignment and movement, but also for our feelings of well-being. As we gauge its ease or non-ease from deep in the belly, tension in the psoas affects us on a deeply emotional level; it acts as a messenger to and from the brain and stores responses to replay them when we remember, imagine or revisit situations that cause us difficulty.

Adding some simple movements and sensitivity to your exercise programme can make the difference between creating more tension and finding a fluidity and refinement of movement that feels in concord with your natural body needs.

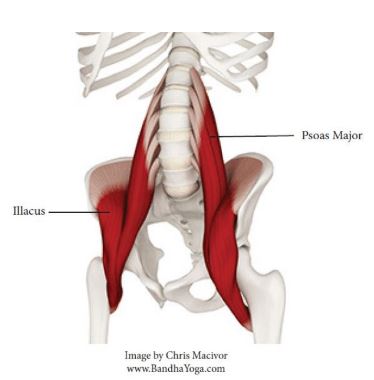

The Psoas Muscle

The psoas is a multi-joint muscle, attaching to many different bones and joints up from the thigh bones (femur) through the pelvis and up to the whole of the lower spine (lumbar L1-L5) and the 12th thoracic vertebra. Among its many functions, it is part of our central body support, stabilises the lumbar spine (lower back), keeps the sacro-iliac joint in the pelvis from being too loose (a source of lower back pain for many) and is used in hip rotation and walking. It is also a key part of our breathing apparatus as it connects up into the diaphragm and is instrumental in changing our breathing patterns in response to stress.

Thomas Myers, author of Anatomy Trains, says he considers the psoas a triangular muscle, with the upper portion acting as a lumbar flexor (bending over) and the lower as a lumbar extensor (lengthening the lower back). When these actions are in balance, our lower backs can sit in happy neutrality and we can move from the centre with ease, grace and lack of pain or tightness. This is where the psoas naturally elongates and falls back towards the spine.

Modern Psoas Issues

Any activity or sedentary habit that over-emphasises flexion in the psoas – ie drawing the knees in towards the chest – such as chair sitting, driving or squatting can leave the muscle bound into this shape. The resulting tightness can then be felt to pull in different parts along its track for different people. Some feel this as pull and tightness into the lower back, other higher up in the diaphragm and tightness of breathing. When tight thigh muscles are also involved the pull can be also felt further down with less opening through the front of the hips and lower belly in back bending shapes. This can be a result of activities that involve strengthening the flexing shape alongside exercise eg cycling and running; especially without post-exercise stretching the thighs.

Healthy Psoas Expression

According to the article The Supportive Psoas by Donna Farhi and Leila Stuart, when the psoas can engage and relax appropriately, it can:

- Contribute to integrated movement that emanates from the core.

- Contribute to core stability as well as improvement of spinal function.

- Support feelings of groundedness and centredness.

- Provide open and free access to the core body.

- Encourage feelings of safety, self-reliance, and being in one’s own power.

The authors also lay out the protocol followed in this article for an intelligent connection with the psoas – one that aids its function, rather than just forcing stretching and opening length in the front body (e.g. lunges and back bends) suddenly from a habitual pattern of flexing.

The Emotional Muscle

The drawing in action of the psoas is a key part of our protective, survival response. Humans are unusual amongst mammals in that our predominant bipedal movement displays our most vulnerable, soft, front parts – groin and belly – to the world. These are hidden underneath in most mammals, so that when we feel fear or threat, we have an immediate response to curl in around these areas. This flexing action comes from the psoas and how it is intimately caught up in our habitual patterns of holding tensions, emotional patterns and trauma. Tendencies to hunch and feel shortened in the front body are not just about physical patterns; they are an expression of self-protection and opening in the chest and belly need to be approached with patience, quiet attention, kindness and soft perseverance for the body to open up. Pushing into these patterns can embed feelings of ‘unsafe’ and exercise can be felt as tension rather than release through the autonomic nervous system.

These patterns of protection can be seen through the whole system, particularly constriction in the hamstrings, shoulders, upper back and hips. The psoas is said to be a key part of our psychodynamic stability – how our body and mind are inherently interconnected. When we feel balanced, attuned and at ease we can feel an easy flow and no imposed or perceived separation of the two, but when stress fractures us, we can feel a disconnect between thought, movement and expression.

Creating Movement from the Psoas

The psoas represents a core part of us - how our top and bottom bodies are connected and it is more helpful to view this line to stand up from the insteps, through inner thighs, pelvic floor and up the spine to the roof of the mouth than simply around the abdominal muscles. From here we can root down to the feet to feel emotional support as we stand with ease from the ground.

Simple positions and movements from the ground, ultimately help us stand tall. Between the following exercises, try walking around to see how you feel. A comfortable psoas can allow walking that feels like the legs are moving from right up into the body; even from the spine at the height of the lower ribs (T12), through the psoas to the legs. This can then be taken into exercise where injury and strain becomes less likely and you can move from the centre, rather than feeling like limbs move independent from the centre.

Calming an Agitated Psoas

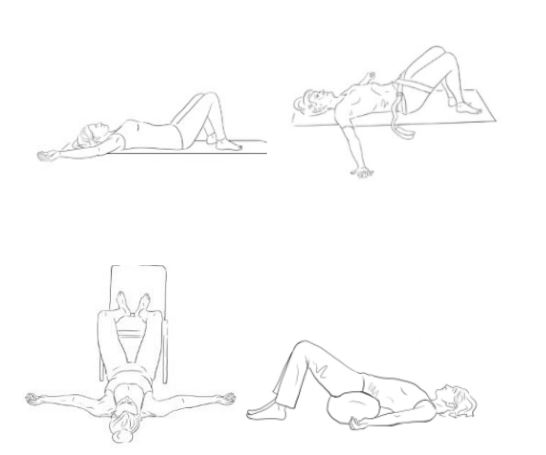

Constructive Rest Position (CRP) is one of the easiest and quickest ways to allow the psoas muscle to fully release, particularly the psoas major which is the main muscle of walking and the warehouse storage for trauma in the body. CRP is a gravitational psoas release as it enables letting go in all the muscles of the back body, of which the psoas is often included.

CRP can reset the physical body as this psoas release allows the spine to return to its natural shape by using the floor for support. As it is a reclined position it also helps to reduce physical tensions and alleviate stresses held both in the body and mind. The pose needs a full 15 minutes of relaxed attention (with soft jaw and eyes) to feel the full benefits.

Do place a folded blanket or low cushion under your skull if your chin doesn’t easily drop towards your throat. If your head drops back, tension from the back of the skull creates mirroring stress in the pelvis and tenses the psoas.

1. Constructive Rest Position (CRP) – place your feet equally weighted between the balls and the heels so that your lower back is soft and comfortable and your thighs do not need to engage to hold the position. If this does not feel possible, try one of the following variations. Also, just placing the balls of your feet onto a cushion or bolster can help

2. CRP with support for lumbar pain – if your thighs feel like they want to drop outwards or your lower back feels a pull, you can tie a belt around the thighs and lower back (or just holding the thighs from falling outwards) can help hold the leg bones in a neutral position. You can also add a support under your lumbar spine if needed.

3. Alternative to help lower back pain – placing your shins onto a chair can be a great alternative for more length in the lower back.

4. Restorative bridge pose for further opening – this is a yoga pose that adds extra opening in the front body and soothing effect for the brain.

NB: for some, in the beginning, CRP can create twitching and spasming as deep release occurs. Breathe deeply, allowing full exhalations if this happens, noticing that you are safe and can allow your outer shell to feel soft to allow tensions to move through

Opening the Hips in Relation to the Psoas

This position opens the psoas as it externally rotates the hip, on one side at a time. It is interesting and informative to lay on your back first to see how your legs feel and then in between each side to feel the inner length created. You can also walk around to feel the depth of release.

You will need a Gertie ball (aka Chi ball), deflated to about a quarter full and placed into the soft part of your groin. Then lay over a bolster with the same side leg drawn up to rotate the hip out. Find a position where you feel you can settle into your hips fairly evenly, without listing too much towards the straight leg, so you don’t have to tense that side where you are lengthening the psoas. Stay for ten minutes on each side, ensuring your head is propped up in a position where your neck is long and comfortable to be able to release in the pelvis.

Feldenkrais Movement for Psoas Opening

From release, we move to hydration and fluidity in the psoas. This movement is part of the Feldenkrais system, where movements follow the patterns that we evolve with from babies learning to move and strengthen. This can help us unravel patterns imprinted in adulthood that are born more of tension and can become more robotic and stuck, thus creating more mind-body stress.

Draw up one knee, moving to really look at it. It is this desire to see that guides babies’ movement and if you follow this through, you can find you move with integrity through from the legs, to hips, to waist, to ribs, to shoulders and neck.Starting in a low sphinx-type pose, find the place where your lower back feels long and not compressed or jammed. For some this is elbows under the shoulders, but for others they need to be further away from the body or even with arms folded in front (as in the second illustration). Have your feet as wide as your lower back needs. This position is lovely for opening the front body after chair-sitting or hunching in its own right. From there the movement is:

- Come back to centre, evening up as you began.

- Move to the other side and alternate each, focusing on allowing fluidity through the whole body.

Lengthening the Psoas with Energy

From those foundations, moving into stronger psoas lengtheners like lunges and back bends in yoga, more dynamic practices and exercise can then strengthen this muscle with the signals that opening is safe.

Yoga offers a body intelligent way to assimilate movement by prioritising relaxation after movement and muscular effort.

Post-Exercise Relaxation

Coming into a curl-in or foetal position like child pose or the supported, soft forward bend shown, counters the front body opening to lengthen the back body. This creates balance and also seals in the message that all in safe in mind-body and that new neural pathways that your psoas can safely open are created. This can help unravel trauma held deep into our physical and emotional core.

Whether you are practising yoga or any other exercise, whenever possible, come to a meditative space where you lay down in Savasana (corpse pose, preferably with knees supported for a soft lower back), to allow healing after putting demands on your system.

References

- Anatomy Trains – Thomas Myers

- Somatics – Thomas Hanna

- The Vital Psoas Muscle – Jo Ann Staugaard-Jones

- Yoga Fascia Anatomy and Movement – Joanne Avison

- Core Awareness – Liz Koch

- Alexander Technique

- Also acknowledgements to Donna Farhi and her Yoga and the Psoas workshop

- The Supportive Psoas – article by Donna Farhi and Leila Stuart