Yoga and Bone Health

Nov 23, 2022

Yoga is an ancient health system that includes a physical practice designed to prepare the body for meditation. Its popularity reflects its universal adaptability to suit individual needs and many modify their practice for changing phases of life. Its emphasis on non-violence, non-competitiveness and self-compassion can allow practitioners to respect the energy and postural needs of their body.

Many people begin yoga to help with back pain and it is no coincidence that they also see improvements in bone health, especially alongside dietary changes of low sugar, less acid-forming foods and higher vegetable intake. The combination of postural improvement, muscular strength and better coordination adds up to improved overall musculo-skeletal health. More balanced breathing patterns also improve circulation to feed oxygen and nutrients to bone cells.

Bone as living tissue

Much of bone health comes down to density, which naturally decreases with age and so increases the risk of debilitating fractures. We reach maximum bone density at around 30 years of age, declining more rapidly from 40. The International Osteoporosis Foundation reports that worldwide, osteoporosis affects around 200 million women. It causes more than 8.9 million osteoporotic fractures annually – for 1 in 3 women over age 50 and 1 in 5 men over 50.

For women, the natural transition of the menopause can compound bone loss, as dropping hormones can result in up to twenty per cent reduction in the first five to seven years after.

Bone is referred to as a ‘rigid organ’ – its dense connective tissue is supportive, but also constantly fluctuating and responding to body needs. Minerals are stored here, as well as fat within bone marrow, white and red blood cells created and buffer systems to control body pH creating a continually breaking down and renewing of the bone matrix.

When this build-up to break-down balance is compromised, firstly bone loss above that of natural aging occurs – osteopenia – and ultimately osteoporosis, often only diagnosed after a fracture. Doctors can test bone density with a non-invasive DEXA (dual energy X-ray absorptiometry) scan.

The research on yoga and bone health

A small study in 2009 called Yoga for Osteoporosis: A Pilot Study by Loren M. Fishman, MD stated in its context that “more than 200,000,000 people suffer from osteoporosis or osteopenia worldwide. An innocuous and inexpensive treatment would be welcome.” As much medical treatment for osteoporosis involves bisphosphonates known to irritate the digestive system, yoga is an obvious solution. It has been practiced by senior citizens (in its present form) for around a century, with many modifications and levels available to teachers.

Fishman’s study, although small, certainly showed positive results. 11 people with an average age of 68, with osteoporosis or osteopenia learned a sequence including Triangle Pose, Downward-Facing Dog and Bridge Pose included in this article. Each was held for 20-30 seconds and the routine took about 10 minutes. This fit in with previous research findings that about 10 seconds of weight-bearing stimulation (see below) is enough to trigger new bone growth. Two years later, Fishman reported that whilst control group members not practising either lost or maintained bone, around 85 percent of the yoga practitioners gained both spine and hip bone density.

This correlates with a study published in the Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand3, where 19 women aged 50-60 undertook a 12 week course of yoga, 3 days a week. Evaluation of bone formation markers showed that “The weight-bearing yoga training had a positive effect on bone by slowing down bone resorption”. An increase in quality of life was also demonstrated by raised physical functioning, general health, and vitality, as well as decreased bodily pain.

Fishman also notes that “Yoga has been shown to reduce back pain, arthritis, and anxiety and to improve gait, neural plasticity associated with motor learning, all capacities that mitigate against the falls that produce osteoporotic fractures.”

The inflammation connection

A sometimes overlooked factor in osteoporosis is inflammation. This protective response is heightened by stress and sugar and interferes with bone mass repair. Stress also lowers beneficial gut bacteria (probiotics), upsetting immune modulation and provoking tendencies to chronic inflammation. Many studies have demonstrated the positive effects of a regular yoga practice on lowering the stress hormone cortisol and associated inflammatory markers such as the cytokine interleukin-6.

Weight-bearing without joint wear

Yoga targets bones in ways that other exercise programmes may not. Activities like weight training, hiking, jogging, tennis and dancing all create force on the bones as we act against gravity. These weight-bearing actions are done on feet and legs and bone adapts to the impact of weight. Yoga postures (when practiced with care and alignment) can damage cartilage and joints less; when poses are held, muscles are lengthened and this pulls on bone, creating the tension that leads to bone growth. As Fishman reported, “By putting tremendous pressure on the bones without harming the joints, yoga may be the answer to osteoporosis.”

This can be seen in a pose like Warrior 2 in the sequence to follow. In an interview for Yoga Journal, Fishman said, “by bending the front knee to 90 degrees, you do more than simply bear weight in the front leg; you magnify the force on the femur (thigh) bone…. Because you’re holding your arms out away from your body, you’re putting a lot more stress on the head of your humerus (upper arm bone) than you would if they were hanging at your sides.”

Overall skeletal health

To view the health of our skeletons, it is key to view the shape of our whole musculo-skeletal structure. For instance, hyperkyphosis, or a hunched back can be commonly seen in the elderly and more prevalent in younger generations with sedentary chair-sitting, computer and smartphone habits. With little opposing action to open the chest and lift up the front spine, the musculature can become reset to collapse in the front body and over-stretch in the back. Helping to coax the thoracic (chest) spine and neck towards their more natural curves helps nurture a supportive structure, reducing compression on discs. This has far-reaching consequences for standing, reaching and the prevention of falls and fractures in the elderly.

In a 2011 paper in the journal ‘Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation’, a review of the literature concluded; “Yoga has the potential to decrease fracture risk in a geriatric population via several mechanisms, including improving balance, reducing fall risk and fear of falls, improving functioning, reducing hyperkyphosis, and improving bone turnover.”

Not just exercise

Yoga is an ancient system of health, including emotional and spiritual – the physical aspects most known today were only introduced to support the ultimate goal of concentration, meditation and a meeting of the individual consciousness with the universal. These deeper aspects invite more commitment to a physical practice and the accompanying breathing focus, mindfulness and attention to other aspects like compassion, plant-based diets and community are all shown to support bone health, through contributing factors like stress-reduction and lowering inflammation.

Working with your body’s needs

Yoga is accessible for all to practice each aspect – physical challenge, stress relief, body system equilibrium – that feeds into skeletal health. Even those who cannot stand can practice upper body positions from sitting.

When bone is healthy, all range of yoga poses can be beneficial and any amount of practice is better than none, with standing poses and those where extra load is placed on parts of the body in other ways – balances, arm balances, inversions, bridge pose, plank pose - having most weight-bearing effect.

When bone loss has occurred, some cautions need to be practiced, for instance, forward bends compress the vertebrae increasing your risk of fracture in those with osteoporosis. A modification with less intense angle can strengthen bone and the muscles supporting it, without exerting strain or further wear (see the downward-facing dog variation below).

As stated in the 2013 study ‘Yoga, vertebral fractures, and osteoporosis: research and recommendations’9, “Ample evidence supports the importance of varied spinal movement for preserving the health and strength of the vertebral bodies. Exercise modifications suitable for high-risk individuals may be counterproductive for those at low risk for vertebral fractures. Yoga therapists are cautioned to not apply a one-size-fits-all approach when working with this population”.

The practice below offers modifications depending on your experience, flexibility and bone health – all options are good practices in their own right, none is better or worse – checking suitability for your individual needs with a yoga therapist, physiotherapist, osteopath or other qualified professional is advised.

Yoga Poses for Bone Loss Prevention

A combination of posturally opening, weight-bearing and actively relaxing postures is a rounded practice for the skeleton. To create the ease that avoids stress, practising with a foundation of mindful attention, soft jaw and free-flowing, spacious breath allows the nervous system to regulate without agitation. As you feel muscle constrict and/or lengthen, breathe into to the process, allowing full exhalations to let the nervous system know you are practising with awareness and protection.

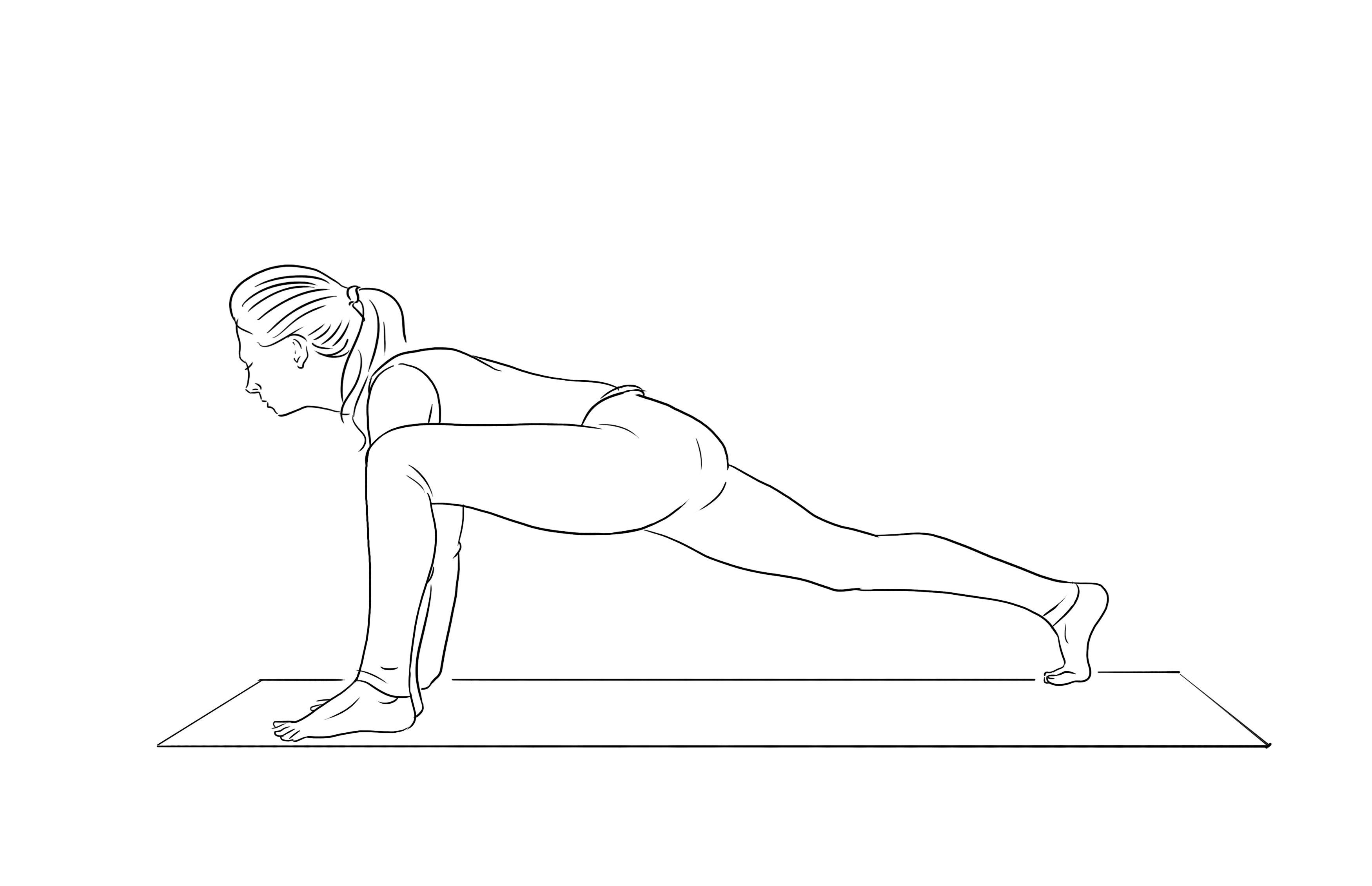

Supta Padangustasana 1

- Gentle version: the lower leg remains bent to lessen the pull on the lower back and allow more progressive opening of the hamstrings. Start here, whatever your level to allow the hamstrings time to open with the flow of your breath. Place a yoga belt around the front of the heel and hold each end, with straight arms and soft shoulders. Support your head with a block or blanket to avoid compression at the back of the neck.

- Deeper version: lengthening the lower leg provides this safe version of a forward bend, lengthens each side of the spine in turn, whilst the spine is supported by the ground for least damage. Breathe fully into all of the sensations as they arise, making space to open up and feel the pose unfolding without the need to react.

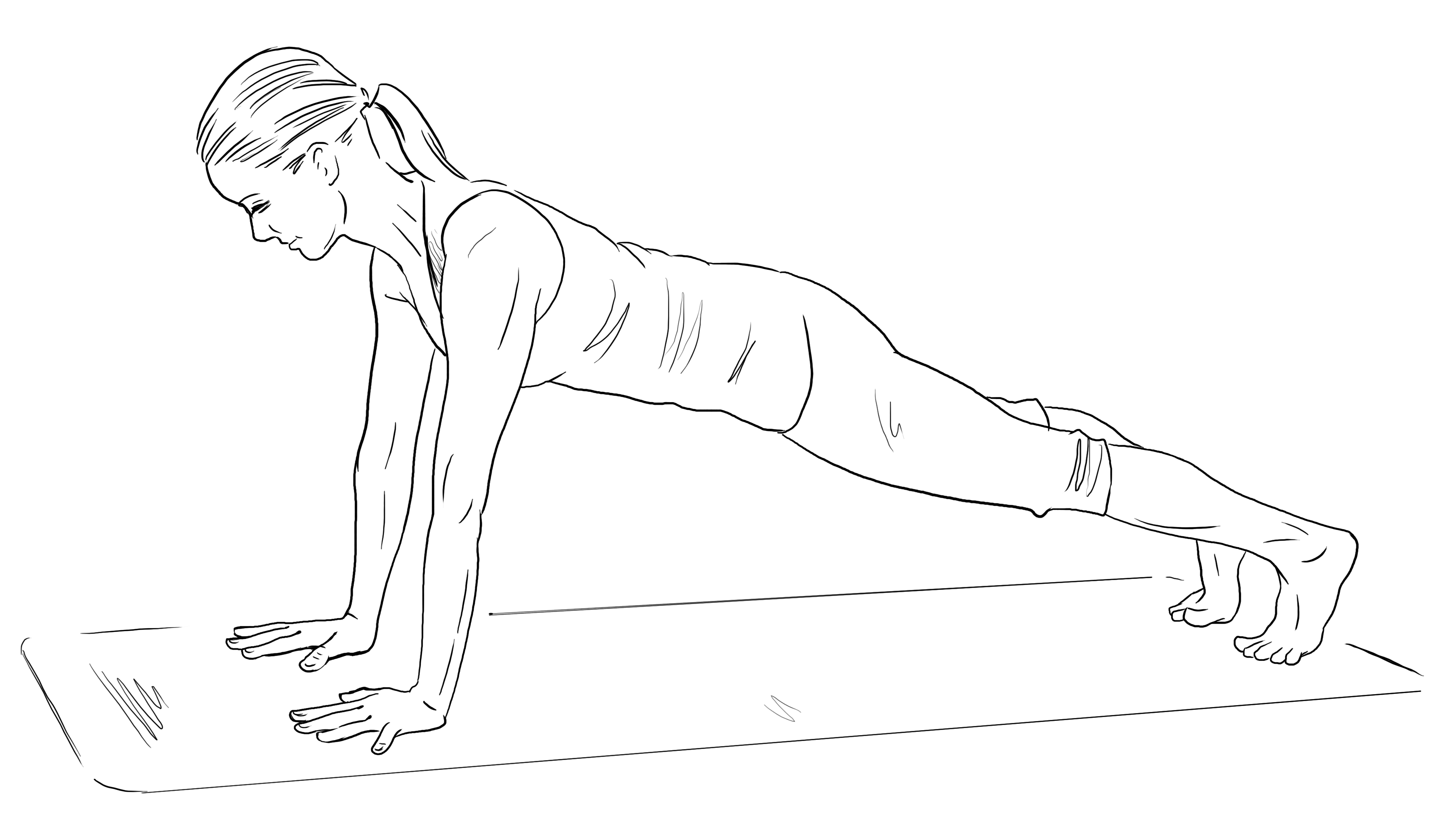

Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog pose)

- Full version: this combination of a forward bending inversion can be strengthening for the spine when enough openness of the chest can allow full push up and back from hand connection from the ground. Rooting into the base of the index finger and drawing back the thighs to lengthen the spine creates space up through the shoulder joints.

- Alternative: where bone loss is present or hunching of the upper back does not allow opening of the front body in this pose, a version against a wall can create an alternative spine length with less force needed. Keep the ears between the arms for a good neck position.

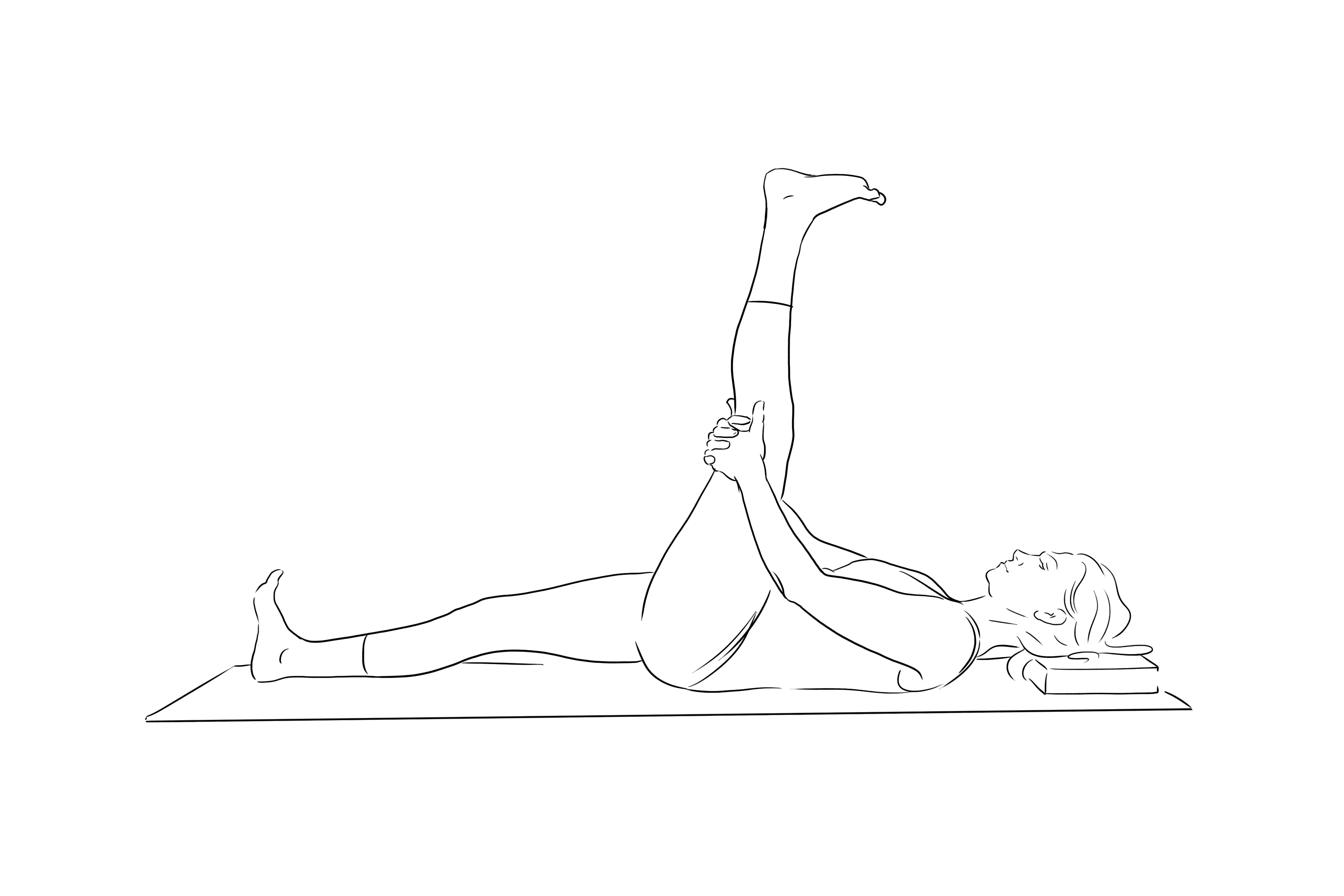

Plank pose

- Full version: plank pose helps strengthen support between the top and bottom body, via strong engagement of the abdominal muscles and drawing the breastbone into the body to prevent just hanging off the shoulders. Holding the whole of the body sideways off the ground is strong weight-bearing. Strong roots into the feet also allow lengthening up to the neck to sit it above the shoulders as when standing; great for neck bone health.

- Alternative: drop your knees for a ‘half’ version of the pose where you are only lifting up the weight of the top body.

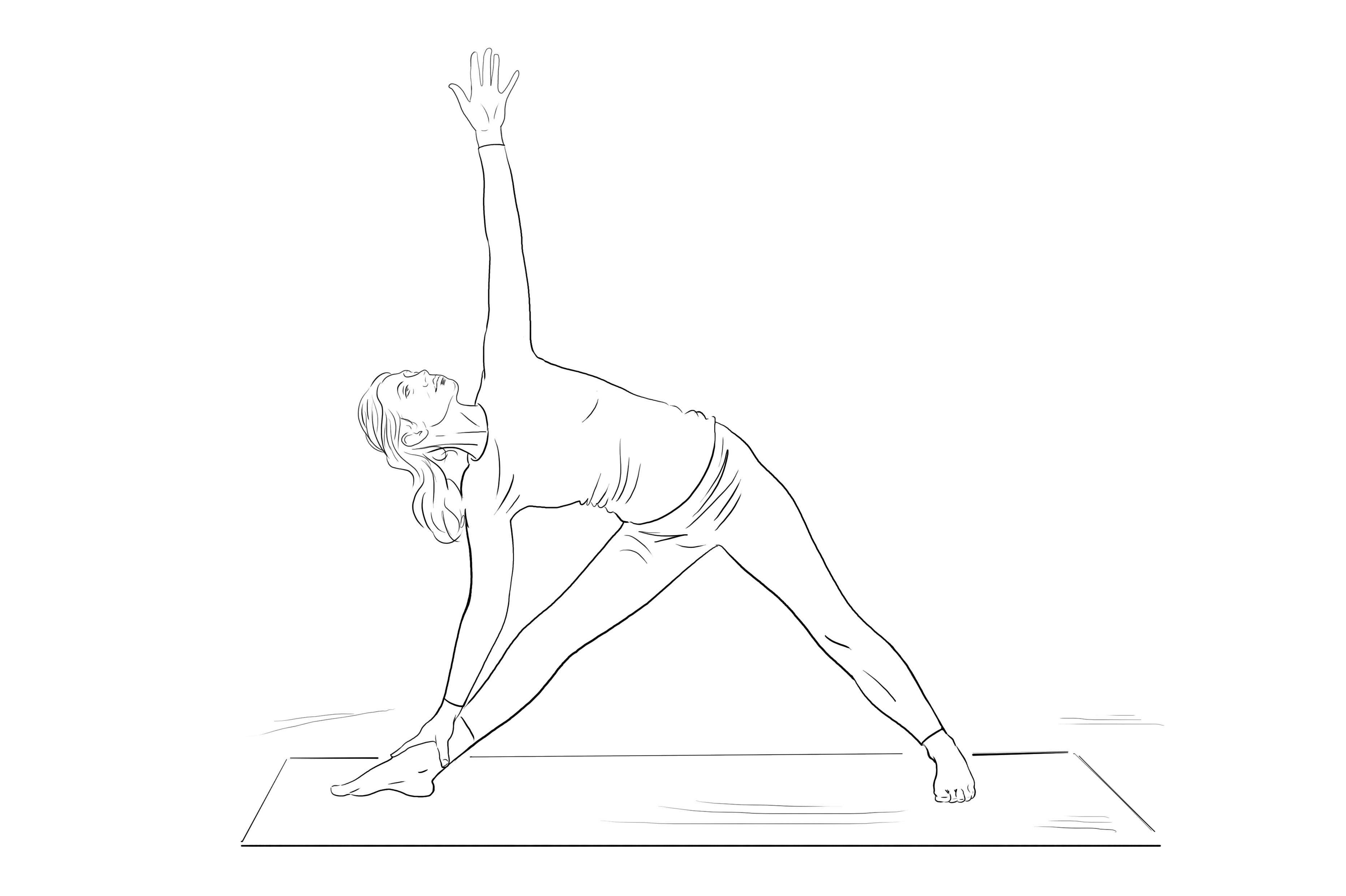

Trikonasana (Triangle Pose)

- Full version: turn the right foot in about 45 degrees and the left foot parallel to the sides of your mat. Lining up the right front heel, knee and sitting bone lets the spine lengthen as we reach out sideways into the pose, without pulling on the lower back. Bring your right hand between the ankle and the knee, not so far down that you cannot open the chest. Look forward to breathe length into the spine as you lift up through the legs. Repeat on the left side.

- Modification: taking the bottom arm to a chair raises the position of the top body, allows chest opening and spine length, which may be difficult if reaching lower.

Virabhadrasana 2 (Warrior 2)

- Full version: turn back to the first trikonasana position, widening your stride if you need, so your right knee doesn’t move past the ankle as you bend into the pose. Keep rotating out the front thigh bone to keep the knee pointing in the direction of the toes for its safety. Turn that foot out a little more if this is difficult. With rib cage above the pelvis, you can lengthen up through the spine whilst sitting equally between the feet.

- Modification: come down just to where your knees and hips feel safe and place your hands on hips to focus on the legs first.

These poses can always be used to ‘bridge’ between other postures as they neutralise the spine.

Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose)

- Full version: from feet hip-width apart, place them close enough in toward your bottom that you can press up to lift the pelvis off the ground, without feeling knee strain. Keeping knees just as wide as your feet and base of your big toe rooted to the ground, ensures you can push to keep the waist long and open the chest.

- Modification: if you have knee issues, place a bolster or stack of blankets under your pelvis so you are not putting pressure on them. This removes weight-bearing, but then becomes a supported back-arch to encourage chest-opening and neck length for spinal health.

Twist choice – seated or supine

- For healthy spine: seated twists need continual heightening of the spine to avoid disc compression as gravity pushes downwards. Uplift is more important than how far we turn. Drawing round from the belly, then chest, then neck allows a smooth spiralling, rather than sudden torqueing at different sites.

- With bone loss: supine (lying) twists are most safe and benefit everyone – upright twists can expose the spine to possible damage, if full lift is difficult. Lying down allows tight shoulders to release and body weight to progressively deepen the pose.

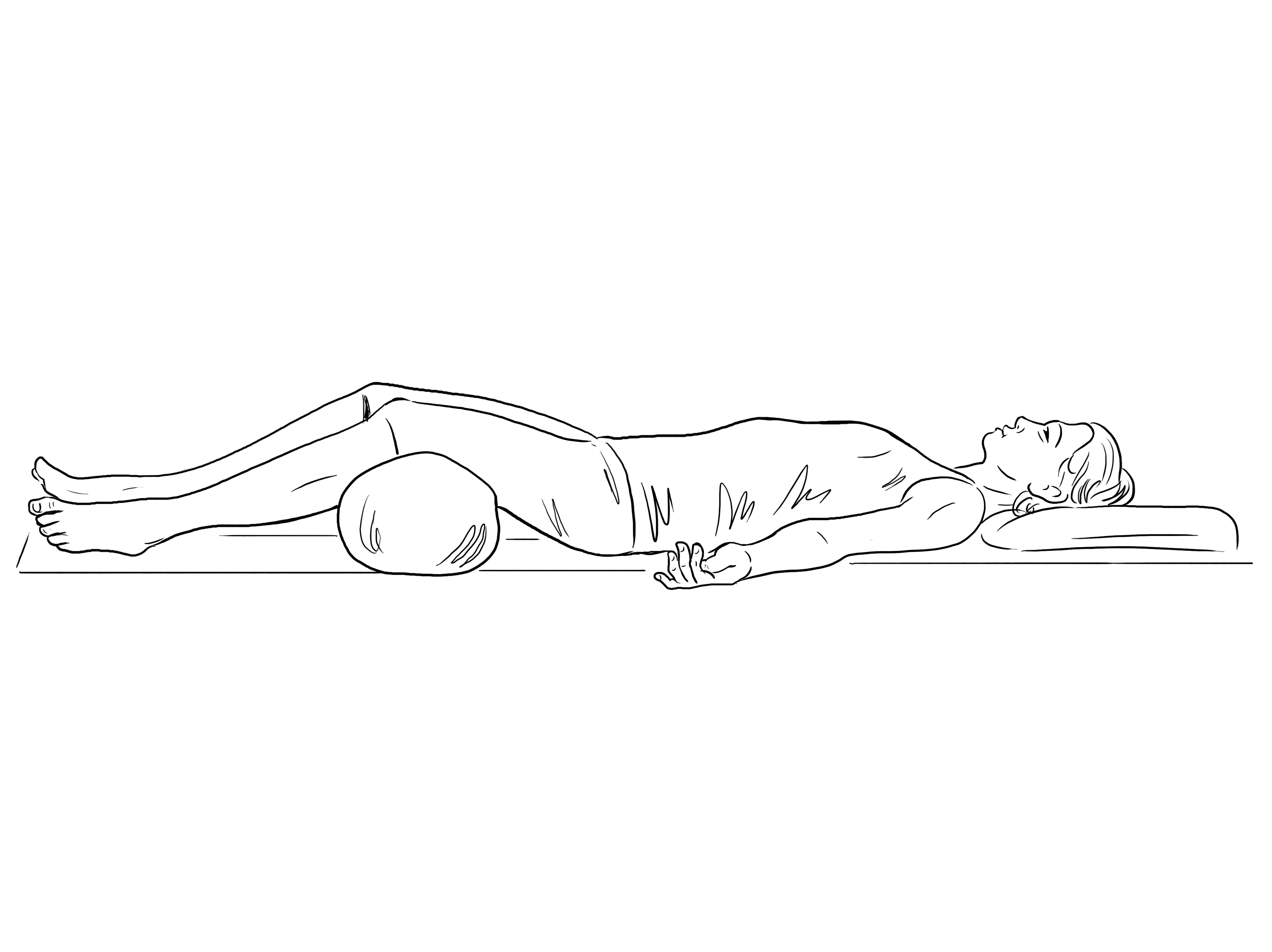

Savasana (corpse pose)

Always finish your practice with Savasana, the deep meditative relaxation that rests muscles and tissues stretched, compressed, twisted and moved. Placing a bolster, cushions or rolled blanket under your knees softens the lower back and allows thigh and psoas muscles to relax more easily. These hold us upright and benefit from restoration to be able to fully support bone.

First published in What Doctor's Don't Tell You Magazine.

Deepen your practice

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars and more...