Exercises for Pelvic Asymmetry

Apr 21, 2022

Pelvic Asymmetry

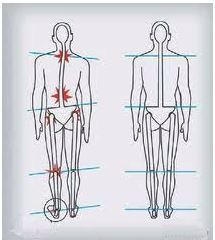

If we look at an anatomical picture of the human skeleton, it would be easy to assume that being fully symmetrical has some kind of normality. Yet, it is actually extremely rare for us to stand equally weighted on both feet, unless instructed to do so in an exercise class. So many people may be unaware that they may have repercussions in the lower back, hips, knees and shoulders from pelvic asymmetry (PA).

The pelvis is the bony bowl-shaped structure at the bottom of the spine; where our legs attach and the cradle for the lower spine bone (the sacrum) to sit into. It can be tilted away from its healthiest positioning in many ways, including forward (anterior), back (posterior), or with rotation, but here we are focussing on lateral or side asymmetry. This is also known as Pelvic Obliquity, where it is tilted to one side, with the spine curved to the opposite. One side of the pelvis is higher than the other, so when standing the top of one iliac crest (felt as the top side of the hip bones) is higher than the other.

This encourages scoliosis or may be a result of this side spinal curve from the centre line. The side that drops may tend to rotate out the same leg and foot, and the head tips in that direction to weight compensate the tilt away from our natural organisation around the midline.

A question longed asked by body experts is if all PA is pathological ie harmful to our function or creating symptoms such as pain and loss of movement. One study setting out to examine this observed that in a healthy group of people aged 18 to 39 with no pelvic or lower back pain, 67.3% of them had PA (Saulicz et al., 2001; https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=854813).

This illustrates how we are built to continually move and quickly adapt to whatever ‘normal’ is presented at any time. As we tend to be repetitious in our sitting, standing and moving states – often over decades and lifetimes - we can quickly create asymmetry.

One study explored how PA can be quickly created, with 321 people showing symmetrical alignment of the pelvis doing many one-sided exercises and showing that if you load weight onto one side of the body only, asymmetry can be quickly created (Journal of Human Kinetics, 2009; 23‐35). The study concluded that; “pelvic asymmetry should be regarded as a physiologic adaptative alteration of the locomotory system to transmission of asymmetrical mechanical loads” and offered division of PA into two types:

‘Fresh’ asymmetry

This usual pattern of PA can come and go as we shift our habits and respond to feeling tightness begin and the need to instinctively balance out. This can occur readily from activities of daily living or movement habits, where we lean into ligaments in a cross-symmetrical way eg from:

- Sitting cross-legged the same way

- Heavy bag on one shoulder

- Driving

- Exercise habits favouring one leg eg in cycling, mounting and pushing off with same each time

- Standing towards one hip habitually

Even gaining awareness of these habits and avoiding or changing how you wear a bag or sit at a desk can have far-reaching effects. Having your exercise posture and equipment evaluated (eg are your bicycle handles in line with the seat?) helps notice and unravel PA setting in as a longer-term issue. As Thomas Hanna (author of ‘Somatics’) stated;

"If you can sense it and feel it, you can change it"

‘Cemented’ asymmetry

When asymmetry ceases to be fresh, there is a tightening of fascial (connective tissue) patterns into new shapes and ways of being that are more resistant to correction. These are frequently accompanied by symptoms, most associated with the LPHC area – the lumbo‐pelvo‐hip complex, where the ‘lumbo-‘ refers to the lumbar spine or lower back. This is attributed to issues in the piriformis and iliopsoas muscles into the buttock and hip.

The good news is that PA can be very responsive to movement that helps correct the imbalance. In a study of 150 people with either C-type or S-type scoliosis (differing shapes of the spine) and difference in leg-length seen in 87%, it was observed that these conditions may be “more often of reversible nature than previously considered” (J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29(7):561-5).

Symmetry could be regained for all patients, from manual, fascial and osteopathic manipulation procedures. A follow-up questionnaire reported that 78% of the patients showed improvement in functional ability and pain. Although this study was discussing bodywork, their conclusion that PA is a common but often overlooked cause of musculoskeletal pain offers a helpful focus, particularly when some simple lifestyle change (such as not crossing legs when sitting) can make such a difference. In the study, 15% of subjects showed immediate or imminent relapse, maybe highlighting the need for both deeper tissue affect and day-to-day changes to avoid recreating these patterns.

How does PA occur?

In the lower back, it is L5 (the lowest lumbar vertebra) and S1 (the top sacral bone) where most spine extension (lengthening) happens and where most of the brunt of any shifts are felt. A shift of the pelvis in any direction can pinch nerves and encourage disc herniation here.

Further down, the sacrum sits into the pelvis at the sacroiliac (SI) joint, the site of much lower back pain. If the pelvis is tilted, it can be too lax on one side and too tight on the other. With more cemented PA, this may relate back to early life, as the sacrum is five separate vertebrae (S1–S5) that begin fusing into one bone around 16-18 years old and are usually completely fused into a single bone by age 26-30.

The SI joint has almost no direct muscular support except the piriformis muscle, which can be a lower back trouble-maker, as the only muscle that attaches directly to the sacrum. It is small and deep into the buttock, starting at the lower spine and connecting to the upper surface of each thighbone. If it is tight on one side, that leg may rotate out more; SI issues are seen in the hip with least flexibility where it will become compressed.

The psoas muscle is a stabiliser for the lower back and joins spine to legs. It is emotionally responsive and if becomes tight and disengaged through chronic stress, trauma and poor postural habits, the secondary stabilisers of the transverse abdominus (TA), multifidus take over. They can become tired and weakened through continual and inappropriate usage.

The TA is a deep muscle layer of the front and side abdominal wall; a key component of ‘the core’. It is much like an inner corset and with PA, becomes bunched up on one side and elongated on the other.

The multifidus is the only muscle that increases strength when it elongates; which we can feel when we lift up through the spine, an action so necessary for helping PA. It also initiates the SI - they co-activate in a loop for lower back stability. The transverse abdominus and multifidus have shown to work in tandem for this support and lower back pain is common when it is interrupted (Man Ther. 2011 Dec;16(6):573-7).

Exercises for unravelling pelvic asymmetry

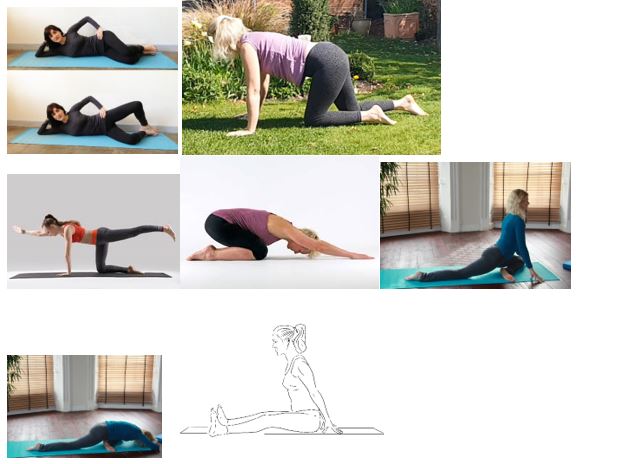

Beginning on the ground, we can explore asymmetrical exercises to feel how we need to find more strength on one side and ease in the other that may have been compensating. Alternating these with symmetrical positions, we can feel a story of our imbalances coming into arrangement around the midline.

- Clamshell – this exercise strengthens buttock muscle to support pelvic symmetry. Lying on your side with knees bent up together, lift the top knee keeping the feet connected. Do 10-20 repetitions on each side, holding the knee up for about 5 seconds. Don’t twist the spine to get more movement, go with the range of motion offered by your hips, which you may notice improved as you do this regularly.

- Free crawling - crawling creates motion across the ‘diagonals’ of the torso; where PA is seen. This us where we 'move out from the centre', so can foster integrated movement from this place out. When we crawl on all-fours, we can feel any movement into tightness here, where the pelvis is not pinned to the ground so no need to pull into the SI at any time you sense tightness, or the restriction of self-protection.

- Sunbird – reaching out from centre side-to-side through opposite arm and leg creates a healthy sideways motion in the pelvis from the naturally extending act of reaching. From all-fours, exhale down towards child pose, then inhale up through the belly to lift the opposite arm and leg out from the centre, drawing the lower ribs in to stabilise the lower. Exhale down to the symmetry of child pose and then to the other side, alternating on each inhalation, before settling down for a minute or so.

- Pigeon pose – this piriformis stretch allows us to breathe space into buttock tightness. From all-fours bring one knee to the back of the same wrist and without any force, move that foot over to where it comfortably comes beneath your groin; this is your natural range-of-motion, so do not strain here. You can hold and breathe into strong sensations, with torso held up or releasing down – feel the difference on each side and breathe acceptance of that.

- Sitting from open hips - our personal natural range can be found sitting in a wide-legged seated position and feeling which natural angle allows the pelvis to feel balanced, maybe with blankets under knees. Lifting through the front spine then helps create space in the pelvis.

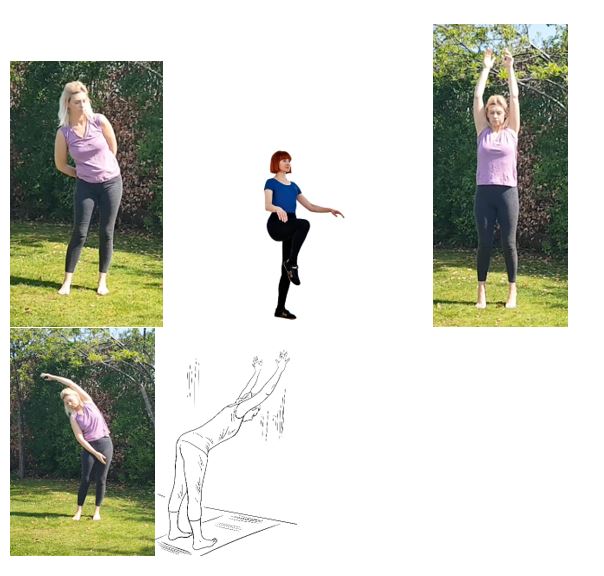

Standing practice

Coming to standing, movement of the pelvis on top of the thigh bones is freed up, which encourages your body to find its natural symmetry, especially where habits have created a new ‘normal’. You can move in the following ways to work within comfortable range of motion and coax out change in tissues, rather than force an imposed will of ‘fixing’ something wrong:

- Rotate the hips, one direction, then the other and switch to notice difference and feel areas which may feel move more easily and those that feel more restricted on each side. Then move the hips in a figure-of-eight motion, one way and then the opposite direction, which may feel less natural and so will help form new neural wiring and reconfigure dominance on one side of the body and brain.

- Lift one knee at a time as you inhale and lift the hands concurrently; as if lifting the knee with invisible strings from your fingers, just as high as feels steady and comfortable. Do this side-to-side in a stepping motion, with a steady focus to notice imbalance but simply let it unravel, rather than try to 'fix' it. You can step forwards and then backwards.

- On an inhalation, lift both arms above your head as you also lift your heels; stabilising with the base of your big toes pressing in to the ground. Exhale back down again.

- On an inhalation lift one arm over the head and bend sideways to lengthen the whole of one side. Exhale that down back to centre, inbetween lifting to the other side, 'bridge' by lifting arms and heels as per the last exercise. Move side to side, lifting in the middle between each side flank stretch.

- Forward bend against a wall to press equally back from both hands (same height from the floor) and draw back the tops of the thighs equally to lengthen both sides of the body.