Balancing for Physical and Mental Health

Jun 22, 2023

Balancing for Physical and Mental Health

Balance is the ability to maintain the body’s centre of mass over its base of support. When this is all working as designed, the fully functioning balance system allows us to maintain clear vision as we move, orient with respect to gravity (ie continually gauge where we are) and determine direction and speed of movement. All of this in the blink of an eye, whilst making the automatic body adjustments to maintain posture and stability in changing activities and conditions.

The challenge that balancing brings constitutes a ‘good stress’ (eustress) for both mind and body. This is a stress (or provocation to a reaction) that prompts us to adapt, focus and have no choice but to stay with the task. It does not tip us over into survival mode or readying for a full-on threat (distress), but does help to raise resilience, where we can handle challenge coming in with more capacity to stay present and open to what the situation needs as it changes.

Balances are a healthy challenge when we breathe fully through them, don’t get caught up in frustrations about whether we ‘can’ or ‘can’t’ do them and let ourselves come back down to a restful state after. That way we are not registering these actions as stressful events in our nervous systems, but rather allowing new neural wiring to create pathways in the brain that train us to become steadier at balancing. In other words, we are cultivating our ability to become more grounded and responsive to subtle changes

What happens when we balance?

When we put ourselves in these positions that essentially destabilise us, we suddenly have to continually modulate our constantly shifting centre of gravity; balancing shows us pretty keenly that our bodies are always in flux as we can feel the inherent full-body movement our breath creates more obviously.

The answer is not to hold our breath so that we are rigidly held in place (thus creating unnecessary tension) but to fully allow breath and soften the mind. When we can let go of attachment to the end point of ‘doing the perfect balance’ or ‘getting it right’, we have much more likelihood of being able to stay. Not caring how long we hold or how much we get into a pose leaves us the space to feel the quality of actually being there.

Balances have long been practiced in many traditional exercise system (eg yoga and t’ai chi) to cultivate steadiness of mind, where it may be in the habit of flitting around with rumination and worry (Arch Phys Med Rehabil.,2014;95(9):1620-1628.e30). When we are balancing, there is little room for focus than other the awareness of where our bodies are in time and space (proprioception).

Balance is also used as a training for those who may feel trauma, chronic stress or injury affecting the vestibular system as symptoms such as dizziness, nausea and vertigo. This is the system within the inner ear that senses motion, equilibrium and spatial orientation – where we are and how to right this to the next moment as we are constantly changing.

Balancing helps to undo these effects of trauma and stress because it brings together the systems that have been disconnected and may render us wanting to move less as our ability to gauge our present moment position and reality are impaired. When we are left not able to trust this sense of ‘presence’, it registers as ‘unsafe’ physically, mentally and emotionally. Balances help regain this clarity and soothe us as we can rely on our sensory input more.

To balance, the sensory systems that provide information about the body’s position in relation to the ground - the eyes (visual), inner ear (vestibular) and skin (proprioceptive) need to feed back to the central nervous system (CNS) about which muscles to activate and when. This integration of sensory input and motor (movement) output to the eye and body muscles helps rewire the healthy orientation and grounding that gives us back agency; an empowering sense of self-control through awareness (Front Hum Neurosci.,2014;8:734).

Balancing is part of life

It is important to remember, that although we can do these exercises that are specifically called balances, normal daily movement involves balancing constantly, just often so small or quick that we barely notice. For instance, as we shift our weight from one leg to another when we go up stairs or reach up on one leg to get something off a higher shelf. If we have become less stable on our feet and feel less trusting of the ground, these simple motions can leave us feeling much more trepidatious in body and mind.

Even the smallest improvement in our balance can create more ‘grounding’ – where our awareness of the placing of our feet to hold us up is more responsiveness and quick to adapt. This can increase confidence in body and mind and less likelihood of falls (BMC Complement Altern Med.,2013;13:8).

This often translates as wobbling, a key part of balancing that we need to breath with, not against. Wobbling is our muscles working to continually right us back to centre. Letting our breath flow, with a steady eye focus is the basis of holding a balance that isn’t brittle and held tightly for a short before stumbling or collapsing. Staying with a balance means allowing the movement of breath (with that wobble!) and feeling it is sustainable because it can move and adapt, like a tree in the wind.

How to practice balancing

Those who feel clumsy or spatially disoriented may shy away from the myriad of emotions that balances bring up, but the more we practice these, the better connections between the somatic (how we move) and central nervous systems become, with a few simple considerations:

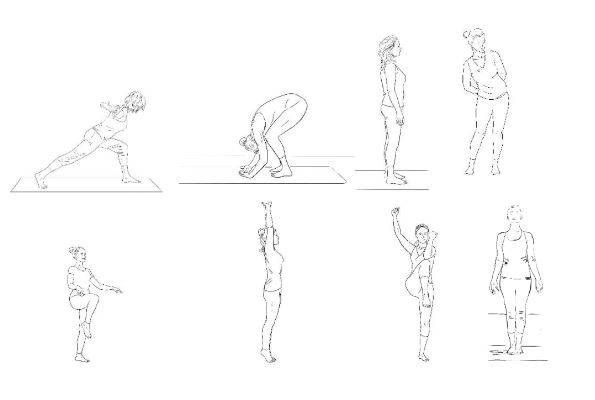

- There are many balance suggestions here, which you can practice as a sequence or pick a few to practice daily. The more you try different positions, the more adaptable your mind-body can become.

- There are moving exercises between the held balances to loosen body tissues needed to then support, and also get you used to shifting your attention as your body needs.

- When you hold static positions, move from the first side to the second, take space to breathe in between rather than rushing at it – especially if side one wasn’t easy. Practice letting go of inner comment or criticism from ‘side one’ and any projections onto ‘side two’.

- Balancing changes on different days, and can be dependent on factors like stress, sleep, worry, medications, injury or alcohol. Rather than judge each time as working or not, approach with curiosity; to gain understanding of where we are in life at this point, with a kind eye.

- All balances can be done with a chair or wall handy for support, but ultimately we are looking practice what it is to challenge this spatial capacity and how our body rises to it. Do use support, but try not to lean all your weight on to it – feel shifting the centre of gravity back to the standing leg, even just occasionally or bit-by-bit.

- Postures here are mostly shown to their furthest points, but every movement can be done in a smaller way, placing the raised foot lower off the ground or onto a chair.

- Practice bare foot where possible to feel responsiveness through your skin on the ground; unclench your toes to progressively drop weight back onto the front of your heel rather than the front foot.

- Steady your gaze on one fixed point, slightly lower to the ground than eye height to quieten comments from the front brain and the whole experience.

- Breathe fully, especially into the out-breath to release the lower jaw, soften the eyes and release any tension in the shoulders.

Preparing your feet

Modern feet can become tight and tense through less natural movement and the wearing of shoes. Regularly moving your feet by rotating ankles, pointing and flexing, all help to keep them pliable and responsive to the ground for good balance.

You can also self-massage your feet daily – which will help how you stand-up from your insteps with most ease – by rolling them over a soft spiky ball, tennis or squash ball to keep the fascia (connective tissue) there malleable.

The practice

- From standing, step one leg back into a high lunge position; feet hip-width apart for stability and just as far as your lower back feels happy. Lean your torso forward and arms out to the side, press into the ball of the back foot to feel length up the whole body. Repeat on the other side.

- Fold into a forward bend with knees bent and arms hanging to decompress your spine and feel the shifting weight on your feet.

- Roll back up to standing, feet hip-width apart with soft knees, to feel most stability with your heels under your sitting bones; tops of thighs above ankles, shoulders above hips and ear above shoulders for our most easily calibrated standing position.

- Circle the hips in one direction and then the other; feeling the inner channels of the legs and up into the hips, groin and belly – where we stand up through when balancing. Come back to the last pose (simply standing) to settle the breath and hip circling to loosen tissues between the following balances.

- Lift one bent leg at a time, raising both hands simultaneously as if lifting the knee with strings. Move side-to-side, inhaling the knee up and exhaling to place back down on the ground; let the eyes follow the movement of the hands. Just come up as far as you retain a sense of grounding on the standing foot, and easy breath.

- On an inhalation, raise both arms out to the side and up, lifting the heels as you go. Exhale the arms and heels back down. Follow just behind the breath, pressing down the ball of the foot to help stabilise the foot into the centre line. Finally hold the pose with fingers interlinked, palms reaching up to the sky and eyes steady. Come down with slow and steady breath.

- Lift one knee and bring the opposite elbow towards it with the inhale. Exhale back to standing and move side-to-side. This cross-lateral (across the centre and different on each side) motion helps to focus the mind and help both sides of the brain work together; good for balance and mental health.

- Now standing feet together rather than apart, feel how more effort is required to maintain stability with a smaller stance; already this has a balancing effect.

- Lift one foot off the ground holding the shin into your chest, feeling how this prompts an uplift through the other, standing leg. Gather in the hip of the standing leg to draw in towards centre and support easier rise upwards as you balance; do the other side. You can also do a lower version with the lifted foot onto a chair seat.

- Back to the first side, lift the foot and rotate the bent leg outwards in circles – as small or large as feels appropriate. If balance is tricky, you can touch the toes to the ground between circles and keep as low as you need. Stay on this side to:

- Draw that lifted foot in towards the other leg to come into tree pose. The foot can be into the thigh, or lower onto the calf or toe touching the ground or on a low stool; but not pushing into the knee joint. If foot in contact with the leg, press where they meet together to lift up through the midline. Keep active in the instep and loose in the toes on the standing leg for balance. Move nos. 10 and 11 to the other side.

- Coming back to the first side, lift up the first leg again; out behind you with that foot parallel to the ground, bottom arm hanging or onto a chair seat. Look downwards for balance and rotate the chest to the sky; repeat on the other side.

- Draw the first leg into the chest and rotate towards it, opening the other arm out behind you or placing that hand onto your lower back. You can also do this twist with the foot placed on a chair. Rotate slowly to the other side.

- Come back to simply standing for a few minutes to gather things back to centre.

Discover Whole Health with Charlotte here, featuring access to yoga classes, meditations, natural health webinars, supplement discounts and more...